For the latest university project we were asked to produce a cover and 2 double pages for 4 different tales by Hans Christian Andersen.

Fairy Tales have always been a huge inspiration to me and my work so I loved every second of working on this project. Even though I would have enjoyed it more to focus completely on one tale and illustrate the whole thing instead of just interpreting certain parts of four different ones...

Anyway, I learned a whole lot during working on these and am now more certain than ever before that picture books really are what I want to create as an artist. They offer so much expressive freedom and creative choices - it's wonderful.

I'll show you some of the work in progress and also include extracts from the evaluation I had to write, which maybe shed some light onto the thoughts that went into every single illustration.

(For this evaluation we had to write about our own work in the third person so don't wonder why it sounds so stiff now and then..)

Quite

like picture books themselves, the tales of Hans Christian Andersen

also suffer from the common misunderstanding that they are aimed at

young children and in fact, have become very “simple children's

fables (…) in all too many translated editions, retellings, and

media adaptations.” (Feng, 2009). In their original Danish versions

they are “far more sophisticated and multi-layered” (Ibid.),

which is something the illustrations created for this brief were also

supposed to be, in order to add more depth to the English translation

and to create another layer on which to find clues for interpreting

the tales.

(...) Words

and images in most successful contemporary picture books work

actively together to create the book's impact - they collaborate by

“filling each other's gaps, or, of even greater significance,

compensating for each other's insufficiencies” and therefore

presenting a ”unique challenge and opportunity in their treatment

of spatiality and temporality.” (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2001,

p.139). The text no longer serves an “auxiliary role” (Shulevitz,

1985, p.15) but is equally important as the image and should make as

little sense read without the illustrations as those should make

without the text. On top of that “the

best, most lasting books seem to be the ones where the picture book

maker (…) leaves space between word and image for the imagination

to roam.” (Salisbury, cited in Klanten and Hellige, 2012, p.158).

Unfortunately

this was an area unable to explore further within the constrains of

this project, since Andersen's tales are so very descriptive and

detailed on their own and do not require illustrations to fill in any

gaps. It was, however, attempted to create visuals which are not

merely decorative or repetitive of the text, rather adding a new

dimension to it that might not be necessary to understand the

narrative but that encourages another interpretation of the seemingly

obvious actions.

For

the second double spread illustrating 'The Snow Queen' for instance,

the abduction of little Kay by the Snow Queen's majestic sledge, as

it is described in the narrative, was not chosen to be depicted on

the accompanying illustration. Instead the image shows a boy setting

out on a quest for knowledge by himself. He is leaving his home and

family behind, while the 'Snow Queen' is only a part of his

subconscious, created by a monotonous day to day routine, which is

symbolized by her consisting of the smoke – the 'refuse' - rising

from his home town's chimneys. While this is only the visual

interpretation of the illustrator, it is supposed to challenge the

reader/viewer to look at the written word from a different

perspective in order to find their very own interpretation in-between

the lines of the text.

(...) The

illustrations created for this project make conscious use of the

elements the picture book as a medium provides. One of them is the

“superior ability” pictures naturally have to “convey the

spatial position of the character, and especially the mutual spacial

relationship of two or more characters, which often reveals their

psychological relationship and relative status.” (Nikolajeva

and Scott, 2001, p.83).

The

first double spread for 'The Snow Queen' exemplifies this. The boy

Kay is moving away from his once beloved friend Gerda who, in turn,

almost appears to be 'dragged' in the opposite direction. He is

literally walking out of their intimate, shared world on the roof top

by leaving the framed image and moving inside the white margin of the

page.

Another

device this double page makes use of is the relationship between the

facing pages, which is an important compositional detail. “In a

good picture book, the creator uses the tension between verso and

recto to imply movements as well as temporal and causal relations.”

(Nikolajeva and Scott, 2001, p.150). They can either cooperate or

contradict each other, in this case they do the latter by

illustrating the different perspectives from which both children view

the world around them. The gutter of the spread almost aligns with

the gutter between the two touching roofs – we find the same

elements on both sides but on the boy's these are distorted due to

the splinter he received in his eye.

Picture

books also are “different

from works of art in their composition, since every picture in a

picturebook (except perhaps the last one) is supposed to encourage

the viewer to go on reading.” (Nodelman, cited in Nikolajeva and

Scott, 2001, p.152). A good way to achieve this is by including a

so-called 'page turner' – a detail,

verbal or visual, that encourages the viewer to turn the page and

find out what happens next.

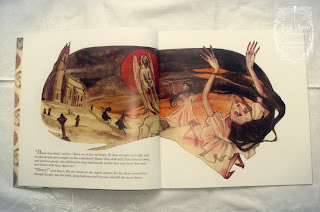

In

the first double spread for 'The Red Shoes' we find such a page

turner in the feet that are seen on the far right side of the recto,

literally leaving this page and intriguing the viewer to follow them.

We

also find 'simultaneous succession' on both double page illustrations

for 'The Red Shoes', which is the depiction of the same character

several times on the same page, suggesting a sequence of separate

moments and conveying movement and thus the flow of time. “Like

blurs and motion lines, simultaneous succession is a narrative

convention that has to be decoded by the viewer” (Nikolajeva and

Scott, 2001, p.140) and can create different effects. In these cases,

it helps to give an impression of uncontrolled movement. The

character is shifted from one position into the next, performing a

bizarre dance she is not able to stop.

The

best device to draw a viewer inside a book is the cover itself. It

was decided upon a circular composition since the nature of the

square format supports this. Andersen's Tales are very close to

nature and many of them feature talking plants and animals.

Therefore, an enchanted forest surrounds the circle containing the

typographic elements.

The

colour palette is deliberately limited, to make sure the visual

details do not overwhelm the written information. You have to look

carefully to make out all the little faces and creatures hidden in

the composition, which hopefully creates interest and serves as a

first interactive viewing experience to draw in the attention of the

viewer. This also is in keeping with the very nature of Andersen's

tales, that challenge you to look closer for hidden meanings and

symbols within them.

The

consideration of the font used for the cover was also very important

since it “occasionally

can affect our understanding of the book.” (Nikolajeva and Scott,

2001, p.245).

Twisted, interwoven vines and twigs were chosen to form the title

'Fairy Stories' and evoke the overall forest theme of the cover as

well as the twisted fates of most stories characters and therefore

help to enhance the book's message.

I hope I was able to give you a little insight in how I work. If you have any further questions, please don't hesitate to ask!

All the best, Anja

Bibliography

Klanten, R. and Hellige, H. (2012).

Little Big Books: Illustrations for Children's Picture Books.

Berlin: Die Gestalten Verlag GmbH & Co.

Nikolajeva,

M. and Scott, C. (2001). How Picturebooks work.

Oxon: Routledge.

Shulewitz, U. (1985). Writing with

Pictures – how to write and illustrate children's books. New

York: Watson-Guptill Publications.